Wow, what a world we live in!

It’s a New Year. And, we face a level of risk and uncertainty that I’ve not experienced since the Cuban Missile Crisis. My father is in the hospital, facing difficult decisions about surgery. My plans for the next weeks are completely subject to events. It can feel that there’s not much ground to stand on.

We are all constantly sensing and reacting to what is going on around us. When things are difficult or chaotic, this can be triggering in many ways. Our inner condition is sometimes completely invisible to us. More often, we just believe that our impatience, urgency, fragmented attention and tight shoulders are the inevitable results of our circumstances. We tell ourselves that we’ll take some time off when the project is complete. Or when our new team member gets up to speed. And, we endure.

We miss the fact that our taking on the condition of the system makes us part of the problem. To the extent that the system around us being chaotic or fragmented means that we are chaotic and fragmented internally, we have lost the boundaries that distinguish us from the system. Our nervous system has become inseparable from the organizational culture and the system dynamics around us. We have lost our perspective, and with it, our capacity to be useful.

This, from a client engagement a few years ago:

I worked with a leader a few years ago who had established an audacious business goal with her team. Ruth was a brilliant and charismatic leader, but in spite of her stellar track record in a very specialized role, also harbored inner doubts about her qualifications, and feared that she’d be “found out.” The stakes were high for her whole team.

In an unconscious effort to prove herself and accelerate the initiative, Ruth often dominated her tense and fast-paced team meetings. She interrupted, taking over others’ ideas, creating re-work, and disenfranchising team members in the meantime. This hyper-driven results orientation was adding to the stress in the system, and incurring significant costs in performance, workload, and team members’ ownership of the business goal.

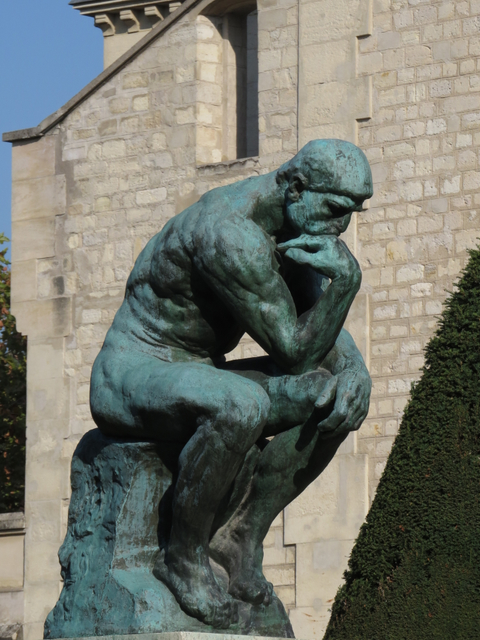

One of the great discoveries of the human condition is that we all have the capacity to direct and organize our attention in ways of our own choosing. We can de-link our inner condition from our outer circumstances.

De-linking our inner state from our context gives us the freedom to represent and embody something entirely new within the systems we intend to influence. We can become an antidote to reactivity. We can be both a symbol and an instigator of a different way of being.

De-linking provides the freedom to choose an organizing principle, an inner state, that is in fact helpful and supportive of the future we intend to invite. We become internally congruent with a value, a cause, a destination that matters to us. This freedom gives us the possibility of becoming ever more intentional about what we take a stand for.

It is crucial that we embody what matters to us. Embodied leadership is how we turn minute firings of neurons into dams, books, trips to the moon, lasting relationships, financial success, and social justice. A future we care about. A culture of curiosity and experimentation. Relationships that are compassionate and supportive.

As I write this, I am awaiting a call from the hospital in New York where my father is facing a difficult treatment decision. There is no question about where my embodied commitment lies. I have a very busy couple of weeks ahead of me. And, if he chooses to have surgery, I’m going to be with him.

I am fully congruent in this. Sure, there are complexities that will need to be managed, events rescheduled or cancelled, and consequences. But, for me, that’s just details. My priorities are clear. I am going to be with my father.

Holding the focus of what we care about is not simply a matter of a mental picture, or a set of words that describe what is important to us. It’s a matter of taking these things in so that we experience them as a felt state, as an inner condition, as an organizing principle.

Ruth was prime for coaching. She intuitively knew that she had become part of the problem and recognized that she needed to shift something. Over time, she began to see how she was adding stress to the system. She experimented with replacing the old narrative that it was “all up to her” with a new narrative that her “team had the chops to deliver” on this goal. She began to organize her attention, and actions, around the assumption that her team could solve most of the big strategic and resource deployment issues that they faced. She didn’t have to provide constant motivation.

Embodying this new narrative took time and practice. Ruth increasingly saw her urge to interrupt, and let it pass. As she held back more and more, she also explicitly communicated her confidence in her team’s resourcefulness. She settled her own internal state, which in turn helped team meetings become more relaxed, productive, and creative. She asked questions, sat back in her chair rather than leaning forward, and allowed pauses and silence where previously every moment had been pressured and packed.

She extended calm confidence into the team environment. They in turn stepped into this new space in astonishing new ways.

Here’s the key. The behaviors that become problematic for us as leaders were acquired previously in our lives in conditions that no longer exist. But, because these behaviors worked at the time, they became embodied as tendencies that tend to emerge under pressure and stress now, decades later.

We can harness the same mechanisms of neuroplasticity and embodied learning to develop and integrate new congruent states, organized around commitments, futures and values of our own choosing. When we practice in this way, we cultivate useful and resilient states that are available to us both now and in the future.

- What habits do you engage in that actually reinforce unhelpful dynamics in your relationships?

- What resourceful internal state do you wish was available when this happens?

- What conditions produce this state? And, how might you practice it when those conditions are not present?