Many years ago, when I first entered the Presence-Based Coaching work as a student, Doug offered three specific distinctions that I found very useful at the time of my professional stretch to learn to be a coach. These same distinctions have been bubbling up recently in my memory for re-examination. I am finding them to be once again useful and timely. The three perspectives are: what I know, what I don’t know, and what I can’t know (the unknowable).

I’ve been facing squarely into my own personal development work this last year, necessitated by Doug’s untimely death from cancer in 2018. I am witnessing my professional expansion towards a newer identity that is shifting to be a bit bigger. The conditions around me have been supporting the growth of this new sense of myself. I have needed to evolve in order to hold a more forward role in the business as a newly minted solo leader. And the business itself has been crossing uncharted terrain, moving towards the capacity to sustain this substantial body of Presence-Based work without its living founder. I am grateful for a highly committed community of our PBC Advisory Board, who have been holding space and creating opportunities for the latest iteration of the Presence-Based work. This body of work is making its way into a new niche around Leadership Development, its origins from the publication of Doug’s last book in 2018, Presence-Based Leadership.

My Personal Approach to What I Know, What I Don’t Know, and What I Can’t Know

These three distinctions of what I know, don’t know and can’t know have been a helpful lens to navigate all of the current transitions I find myself in: personal, professional, business, and the body of the Presence-Based work itself. My hope is that they will speak to a current transition you or your client might be in. Here’s how I’ve been working with them.

As I apply these three distinctions to my current transitions, it feels important to unpack them in terms of which elements belong within each category. My recent practice has been to capture ideas in each segment. As I articulate which element belongs in each category, I notice I am moved to add a place for the specific “challenges” each perspective brings with it. The “challenges” section further clarifies which of my particular habits tend to arise as a primary strategy to deal with each grouping. These challenges also represent another view or learning edge for me to work with along the way. I’ve presented the details of my exploration below. It is my hope that my personal content may spur new ideas, insights and support for your own, or your client’s, transitions.

What I know: I love and feel deep resonance with the Presence-Based work. It fits my passions and skills well and I have developed adeptness in it and embodiment of it. I admire its power to impact those who offer/practice this methodology as coaches or experience it as clients. I relish the joy I feel as someone I am working with has an insight that shifts them towards what most matters to them. I align with my purpose through this material. I enjoy being of service using presence to support others to become their biggest and best selves.

- The challenge here is to remember these “knowns” as organizing principles in my day to day, detailed oriented life! I often get pulled into the weeds and daily grind of scheduling, business operations, even teaching deliveries and travel that can feel compressed time-wise. It is an ongoing challenge to be in my regular grounding practices on the road. Getting some insights here connected to my habit of not taking enough rest/recovery time and the need to add more space to my calendar.

What I don’t know: The demand for coaches, and organizations who train them. How the Presence-Based Leadership material will be received by leaders (and their coaches). How this Presence-Based work will evolve and what it may ultimately look like/turn into over the years with various iterations and contributors. What disruptors, innovations and market demands (e.g. technology) may affect the way training is even done or preferred in the future.

- The challenge here is to manage my feelings of anxiety and overwhelm around this, especially when facing into something that calls for a stretch beyond what’s usual or comfortable or easy. To pull back my attention into the present moment when it goes too far into the future and stays stuck in planning or forecasting. Or practice bringing my attention to present time when I notice I am located in the past, getting pulled into (and take to be real) my limiting narratives around deficiency or comparison.

What I can’t know (the unknowable): My health (or the health those whom I love). The world’s political, economic, environmental, technological and business contexts. What new local or global trends may emerge that will affect coaching, coach training and leadership development work. Will this Presence-Based Coaching and Leadership work, which seem so vital and needed today, still be relevant down the road?

- The challenge here is remaining grounded around my purpose and passions (what I know). To practice coming back to center when I lose a sense of myself or when I face into what I can’t control or can’t be controlled. It’s helpful to remember that life is quite short and fragile (Doug’s death brought this fact home to me in an immediate and personal way). It’s also a wake up to realize that I am two thirds of the way through my own life! This unknowable space calls for trust that everything is, indeed, working out in the best possible way, despite the many vicissitudes of life as a human on this planet, in this time-frame. Sometimes, my mind creates doubts when facing into immediate difficulties. And sometimes, as I do my regular practices of yoga and meditation, I am able to rest into the felt-sense of trust in my body and the inner knowing that life’s journey is unfolding with precision for my own development. I am able to surf the waves with a sense of ease and allowing.

Clarity Arises from Closer Inspection

Even though the buckets of the three distinctions are an artificial parsing out of a reality that is actually arising as one dynamic flow, I find there is something to be gained from naming each challenge. This allows me the room to sense a bit deeper within each distinction. As I do this, something arises and changes internally for me that produces clarity.

For example, as I sense into the “what I know” category, I feel a sense of steadiness; an internal confidence that these elements actually represent the deeper and supportive ground as I move forward. As I contemplate “what I don’t know,” I remember the possibility of finding some sort of external support to fill in the gaps. And I can generate internal support by actually framing the opportunity of learning and practicing something new. As I generate the list of “what I can’t know,” what’s actually unknowable — surprisingly, it has the effect of relaxing me and my nervous system. Somehow letting go of trying to control what’s not under my control feels like a bit of relief and liberation. Maybe I don’t have to work so hard! Why spend energy and effort on what’s not controllable? With that awareness, an urge arises to focus back towards “what I know” as a solid ground. And looking back on “what I don’t know” from this sense of solid ground, there is a desire to wake up. I want to pay attention to any early signals of change, to include others for additional perspectives (and to challenge my narrative that I have to do it alone). And I wonder what exactly I do want to learn next that feels exciting and rich and needed now?

Using the Known, Unknown, and Unknowable to Navigate Complexity

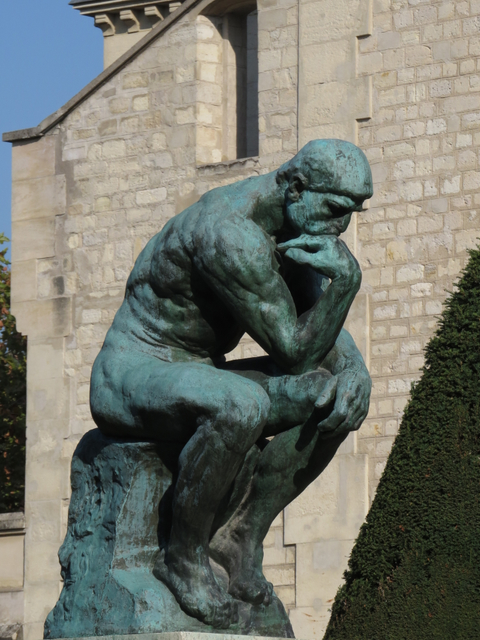

These distinctions are useful as well in navigating complexity (this topic is a significant part of the Presence-Based Leadership work). Complexity includes many layers or levels of systems that are involved in any pattern. The reality is that complex adaptive systems (e.g. humans!) don’t operate within cause and effect principles.

In the domain of complexity, occurrences are not predictable or knowable in advance (only in hindsight). It turns out that being able to be present with, and even rest in, what’s ambiguous and unknown, is a very helpful perspective. And inhabiting yourself in a way that’s present, connected, grounded and flexible, is very useful for both leaders and coaches!

Of course, I suspect many of you might be facing complexity or are in a transition in your own life, as I was when learning to become a coach, and am now learning to lead this Presence-Based work. Perhaps you are facing things like the restructuring of your company, or a health crisis, or a relationship break, or adult children leaving home, or aging parents needing more of your attention. And our clients experience these transition spaces as well, either personally or inside organizations with new leadership demands, more responsibilities, changing business and technology environments, scaling up or down, mergers.

Some Questions to Play With

I offer these questions to you to play with anytime, and perhaps especially during transitions or when dealing with complexity. You can choose any particular area that seems up for you or your clients right now. Let us know what you discover!

- What do I know?

- What is it that I don’t know?

- What is it that I can’t know (the unknowable)?

- What are the specific challenges to each of these distinctions?

- And what do you notice in your experience (body, emotions, inner story) as you sink into each one of these distinctions?

- What clarity emerges from this exercise?